Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

General Information About Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

ALL (also called acute lymphocytic leukemia) is an aggressive type of leukemia characterized by the presence of too many lymphoblasts or lymphocytes in the bone marrow and peripheral blood. It can spread to the lymph nodes, spleen, liver, central nervous system (CNS), testicles, and other organs. Without treatment, ALL usually progresses quickly.

Signs and symptoms of ALL may include:

- Weakness or fatigue.

- Fever or night sweats.

- Bruises or bleeds easily (i.e., bleeding gums, purplish patches in the skin, or petechiae [flat, pinpoint spots under the skin]).

- Shortness of breath.

- Unexpected weight loss or anorexia.

- Pain in the bones or joints.

- Swollen lymph nodes, particularly lymph nodes in the neck, armpit, or groin, which are usually painless.

- Swelling or discomfort in the abdomen.

- Frequent infections.

ALL occurs in both children and adults. It is the most common type of cancer in children, and treatment results in a good chance for a cure. For adults, the prognosis is not as optimistic. This summary discusses ALL in adults. For more information, see Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment.

Incidence and Mortality

Estimated new cases and deaths from ALL in the United States in 2025:[1]

- New cases: 6,100.

- Deaths: 1,400.

Anatomy

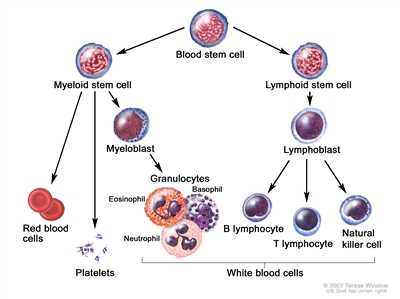

ALL presumably arises from malignant transformation of B- or T-cell progenitor cells.[2] It is more commonly seen in children but can occur at any age. The disease is characterized by the accumulation of lymphoblasts in the marrow or in various extramedullary sites, frequently accompanied by suppression of normal hematopoiesis. B- and T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia cells express surface antigens that parallel their respective lineage developments. Precursor B-cell ALL cells typically express CD10, CD19, and CD34 on their surface, along with nuclear terminal deoxynucleotide transferase (TdT), while precursor T-cell ALL cells commonly express CD2, CD3, CD7, CD34, and TdT.

Blood cell development. A blood stem cell goes through several steps to become a red blood cell, platelet, or white blood cell.

Molecular Genetics

Some patients presenting with acute leukemia may have a cytogenetic abnormality that is cytogenetically indistinguishable from the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph).[3] The Ph occurs in only 1% to 2% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), but it occurs in about 20% of adults and a small percentage of children with ALL.[4] In most children and in more than one-half of adults with Ph-positive ALL, the molecular abnormality is different from that in Ph-positive chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Many patients who have molecular evidence of the BCR::ABL1 fusion gene, which characterizes the Ph, have no evidence of the abnormal chromosome by cytogenetics. The BCR::ABL1 fusion gene may be detectable only by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) because many patients have a different fusion protein from the one found in CML (p190 vs. p210). These tests should be performed, whenever possible, in patients with ALL, especially in those with B-cell lineage disease.

L3 ALL is associated with a variety of translocations that involve the MYC proto-oncogene and the immunoglobulin gene locus t(2;8), t(8;12), and t(8;22).

Diagnosis

Patients with ALL may present with a variety of hematologic abnormalities ranging from pancytopenia to hyperleukocytosis. In addition to a history and physical examination, the initial workup should include:

- Complete blood count with differential.

- A chemistry panel (including uric acid, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, potassium, phosphate, calcium, bilirubin, and hepatic transaminases).

- Fibrinogen and tests of coagulation as a screen for disseminated intravascular coagulation.

- A careful screen for evidence of active infection.

A bone marrow biopsy and aspirate are routinely performed even in T-cell ALL to determine the extent of marrow involvement. Malignant cells should be sent for conventional cytogenetic studies, as detection of the Ph t(9;22), MYC gene rearrangements (in Burkitt leukemia), and KMT2A gene rearrangements add important prognostic information. Flow cytometry should be performed to characterize expression of lineage-defining antigens and determine the specific ALL subtype. In addition, for B-cell disease, the malignant cells should be analyzed using RT-PCR and FISH for evidence of the BCR::ABL1 fusion gene. This last point is of utmost importance, as timely diagnosis of Ph ALL will significantly change the therapeutic approach.

Diagnostic confusion with AML, hairy cell leukemia, and malignant lymphoma is not uncommon. Proper diagnosis is crucial because of the difference in prognosis and treatment of ALL and AML. Immunophenotypic analysis is essential because leukemias that do not express myeloperoxidase include M0 AML, M7 AML, and ALL.

The examination of bone marrow aspirates and/or biopsy specimens should be done by an experienced oncologist, hematologist, hematopathologist, or general pathologist who is capable of interpreting conventional and specially stained specimens.

Prognosis and Survival

Factors associated with prognosis in patients with ALL include:

- Age: Age, a significant factor in childhood ALL and AML, may be an important prognostic factor in adult ALL. In one study, the overall prognosis was better in patients younger than 25 years; another study found a better prognosis in patients younger than 35 years. These findings may, in part, be related to the increased incidence of the Ph in older patients with ALL, a subgroup associated with poor prognosis.[5,6]

- CNS involvement: As in childhood ALL, adult patients with ALL are at risk of developing CNS involvement during the course of their disease. This is particularly true for patients with L3 (Burkitt) morphology.[7] This complication influences both treatment and prognosis.

- Cellular morphology: Patients with L3 morphology showed improved outcomes, as evidenced in a completed Cancer and Leukemia Group B study (CLB-9251 [NCT00002494]), when treated according to specific treatment algorithms.[8,9] This study found that L3 leukemia can be cured with aggressive, rapidly cycling, lymphoma-like chemotherapy regimens.[8,10,11]

-

Chromosomal abnormalities: Chromosomal abnormalities, including aneuploidy and translocations, have been described and may correlate with prognosis.[12] In particular, patients with Ph-positive t(9;22) ALL have a poor prognosis and represent more than 30% of adult cases. Patients with leukemia and a BCR::ABL1 fusion gene who do not demonstrate the classical Ph carry a poor prognosis similar to those who are Ph positive. Patients with Ph-positive ALL are rarely cured with chemotherapy, although long-term survival is now routinely reported when such patients are treated with combinations of chemotherapy and BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Two other chromosomal abnormalities associated with a poor prognosis are t(4;11), which is characterized by rearrangements of the KMT2A gene and may be rearranged despite normal cytogenetics, and t(9;22). In addition to t(4;11) and t(9;22), compared with patients with a normal karyotype, patients with deletion of chromosome 7 or trisomy 8 have been reported to have a lower probability of survival at 5 years.[13] In a multivariate analysis, karyotype was the most important predictor of disease-free survival.[13][Level of evidence C2]

Late Effects of Treatment for ALL

Long-term follow-up of 30 patients with ALL in remission for at least 10 years has demonstrated ten cases of secondary malignancies. Of 31 long-term female survivors of ALL or AML younger than 40 years, 26 resumed normal menstruation following completion of therapy. Among 36 live offspring of survivors, two congenital problems occurred.[14]

References:

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. American Cancer Society, 2025. Available online. Last accessed January 16, 2025.

- Pui CH, Jeha S: New therapeutic strategies for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6 (2): 149-65, 2007.

- Peterson LC, Bloomfield CD, Brunning RD: Blast crisis as an initial or terminal manifestation of chronic myeloid leukemia: a study of 28 patients. Am J Med 60(2): 209-220, 1976.

- Secker-Walker LM, Cooke HM, Browett PJ, et al.: Variable Philadelphia breakpoints and potential lineage restriction of bcr rearrangement in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 72 (2): 784-91, 1988.

- Gaynor J, Chapman D, Little C, et al.: A cause-specific hazard rate analysis of prognostic factors among 199 adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the Memorial Hospital experience since 1969. J Clin Oncol 6 (6): 1014-30, 1988.

- Hoelzer D, Thiel E, Löffler H, et al.: Prognostic factors in a multicenter study for treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. Blood 71 (1): 123-31, 1988.

- Kantarjian HM, Walters RS, Smith TL, et al.: Identification of risk groups for development of central nervous system leukemia in adults with acute lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 72 (5): 1784-9, 1988.

- Lee EJ, Petroni GR, Schiffer CA, et al.: Brief-duration high-intensity chemotherapy for patients with small noncleaved-cell lymphoma or FAB L3 acute lymphocytic leukemia: results of cancer and leukemia group B study 9251. J Clin Oncol 19 (20): 4014-22, 2001.

- Hoelzer D, Ludwig WD, Thiel E, et al.: Improved outcome in adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 87 (2): 495-508, 1996.

- Fenaux P, Lai JL, Miaux O, et al.: Burkitt cell acute leukaemia (L3 ALL) in adults: a report of 18 cases. Br J Haematol 71 (3): 371-6, 1989.

- Reiter A, Schrappe M, Ludwig WD, et al.: Favorable outcome of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood: a report of three consecutive studies of the BFM group. Blood 80 (10): 2471-8, 1992.

- Chromosomal abnormalities and their clinical significance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Third International Workshop on Chromosomes in Leukemia. Cancer Res 43 (2): 868-73, 1983.

- Wetzler M, Dodge RK, Mrózek K, et al.: Prospective karyotype analysis in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the cancer and leukemia Group B experience. Blood 93 (11): 3983-93, 1999.

- Micallef IN, Rohatiner AZ, Carter M, et al.: Long-term outcome of patients surviving for more than ten years following treatment for acute leukaemia. Br J Haematol 113 (2): 443-5, 2001.

Cellular Classification of ALL

The following leukemic cell characteristics are important:

- Morphological features.

- Cytogenetic characteristics.

- Immunologic cell surface and biochemical markers.

- Cytochemistry.

In adults, French-American-British (FAB) L1 morphology (more mature-appearing lymphoblasts) is present in fewer than 50% of patients, and L2 morphology (more immature and pleomorphic) predominates.[1] L3 (Burkitt) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is much less common than the other two FAB subtypes. It is characterized by blasts with cytoplasmic vacuolizations and surface expression of immunoglobulin, and the bone marrow often has an appearance described as a starry sky owing to the presence of numerous apoptotic cells. L3 ALL is associated with a variety of translocations that involve the MYC proto-oncogene and the immunoglobulin gene locus t(2;8), t(8;12), and t(8;22).

Some patients presenting with acute leukemia may have a cytogenetic abnormality that is morphologically indistinguishable from the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph).[2] The Ph occurs in only 1% to 2% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), but it occurs in about 20% of adults and a small percentage of children with ALL.[3] In most children and in more than one-half of adults with Ph-positive ALL, the molecular abnormality is different from that in Ph-positive chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Many patients who have molecular evidence of the BCR::ABL1 fusion gene, which characterizes the Ph, have no evidence of the abnormal chromosome by cytogenetics. The BCR::ABL1 fusion gene may be detectable only by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis or reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction because many patients have a different fusion protein from the one found in CML (p190 vs. p210).

Using heteroantisera and monoclonal antibodies, ALL cells can be divided into several subtypes (see Table 1).[1,4,5,6]

| Cell Subtype | Approximate Frequency |

|---|---|

| Early B-cell lineage | 80% |

| T cells | 10%–15% |

| B cells with surface immunoglobulins | <5% |

About 95% of all types of ALL (except Burkitt, which usually has an L3 morphology by the FAB classification) have elevated terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) expression. This elevation is extremely useful in diagnosis; if concentrations of the enzyme are not elevated, the diagnosis of ALL is suspect. However, 20% of cases of AML may express TdT; therefore, its usefulness as a lineage marker is limited. Because Burkitt leukemias are managed according to different treatment algorithms, it is important to specifically identify these cases prospectively by their L3 morphology, absence of TdT, and expression of surface immunoglobulin. Patients with Burkitt leukemias will typically have one of the following three chromosomal translocations:

- t(8;14).

- t(2;8).

- t(8;22).

References:

- Brearley RL, Johnson SA, Lister TA: Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in adults: clinicopathological correlations with the French-American-British (FAB) co-operative group classification. Eur J Cancer 15 (6): 909-14, 1979.

- Peterson LC, Bloomfield CD, Brunning RD: Blast crisis as an initial or terminal manifestation of chronic myeloid leukemia: a study of 28 patients. Am J Med 60(2): 209-220, 1976.

- Secker-Walker LM, Cooke HM, Browett PJ, et al.: Variable Philadelphia breakpoints and potential lineage restriction of bcr rearrangement in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 72 (2): 784-91, 1988.

- Hoelzer D, Thiel E, Löffler H, et al.: Prognostic factors in a multicenter study for treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. Blood 71 (1): 123-31, 1988.

- Sobol RE, Royston I, LeBien TW, et al.: Adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia phenotypes defined by monoclonal antibodies. Blood 65 (3): 730-5, 1985.

- Foon KA, Billing RJ, Terasaki PI, et al.: Immunologic classification of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Implications for normal lymphoid differentiation. Blood 56 (6): 1120-6, 1980.

Stage Information for ALL

There is no distinct staging system for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). This disease is classified as untreated, in remission, or recurrent.

Untreated ALL

For a newly diagnosed patient with no prior treatment, untreated ALL is defined by:

- Abnormal white blood cell count and differential.

- Abnormal hematocrit/hemoglobin and platelet counts.

- Abnormal bone marrow with more than 5% blasts.

- Signs and symptoms of the disease.

ALL in Remission

A patient who has received remission-induction treatment of ALL is in remission if all of the following criteria are met:

- Bone marrow is normocellular with no more than 5% blasts.

- There are no signs or symptoms of the disease.

- There are no signs or symptoms of central nervous system leukemia or other extramedullary infiltration.

- All of the following laboratory values are within the reference ranges:

- White blood cell count and differential.

- Hematocrit/hemoglobin level.

- Platelet count.

Treatment Option Overview for ALL

Successful treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) consists of the control of bone marrow and systemic disease and the treatment (or prevention) of sanctuary-site disease, particularly the central nervous system (CNS).[1,2] The cornerstone of this strategy includes systemically administered combination chemotherapy with CNS preventive therapy. CNS prophylaxis is achieved with chemotherapy (intrathecal and/or high-dose systemic therapy) and, in some cases, cranial radiation therapy.

Treatment is divided into three phases:

- Remission induction.

- CNS prophylaxis.

- Consolidation (also called remission continuation or maintenance).

The average length of treatment for ALL ranges from 1.5 to 3 years in the effort to eradicate the leukemic cell population. Younger adults with ALL may be eligible for selected clinical trials for childhood ALL. For more information, see the Adolescents and Young Adults With ALL section in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment.

Entry into a clinical trial is highly desirable to ensure adequate patient treatment and maximal information retrieval from the treatment of this highly responsive, but usually fatal, disease.

| Disease Status | Treatment Options |

|---|---|

| BMT = bone marrow transplant; CNS = central nervous system. | |

| Untreated ALL | Remission induction therapy |

| CNS prophylaxis therapy | |

| ALL in remission | Consolidation therapy |

| CNS prophylaxis therapy | |

| Recurrent ALL | Reinduction chemotherapy followed by allogeneic BMT |

| Blinatumomab followed by allogeneic BMT | |

| Inotuzumab ozogamicin followed by allogeneic BMT | |

| Palliative radiation therapy | |

| Dasatinib | |

| Revumenib | |

References:

- Clarkson BD, Gee T, Arlin ZA, et al.: Current status of treatment of acute leukemia in adults: an overview of the Memorial experience and review of literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 4 (3): 221-48, 1986.

- Hoelzer D, Gale RP: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults: recent progress, future directions. Semin Hematol 24 (1): 27-39, 1987.

Treatment of Untreated ALL

Treatment Options for Untreated ALL

Treatment options for untreated acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) include:

-

Remission induction therapy, including:

- Combination chemotherapy.

- Imatinib mesylate (for patients with Philadelphia chromosome [Ph]–positive ALL).

- Imatinib mesylate combined with combination chemotherapy (for patients with Ph-positive ALL).

- Supportive care.

-

Central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis therapy, including:

- Cranial radiation therapy plus intrathecal (IT) methotrexate.

- High-dose systemic methotrexate and IT methotrexate without cranial radiation therapy.

- IT chemotherapy alone.

Remission induction therapy

Sixty percent to 80% of adults with ALL usually achieve a complete remission after appropriate induction therapy. Appropriate initial treatment, usually consisting of a regimen that includes the combination of vincristine, prednisone, and an anthracycline, with or without asparaginase, results in a complete response rate of up to 80%. In patients with Ph-positive ALL, the remission rate is generally greater than 90% when standard induction regimens are combined with BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors. In the largest study published to date of Ph-positive ALL patients, 1,913 adult patients with ALL had a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 39%.[1]

Patients who experience a relapse after remission usually die within 1 year, even if a second complete remission is achieved. If there are appropriate available donors and if the patient is younger than 55 years, bone marrow transplant may be considered.[2] Transplant centers performing five or fewer transplants annually usually have poorer results than larger centers.[3] If allogeneic transplant is considered, it is recommended to avoid transfusions with blood products from a potential donor.[4,5,6,7,8,9,10]

Combination chemotherapy

Most current induction regimens for patients with adult ALL include combination chemotherapy with prednisone, vincristine, and an anthracycline. Some regimens, including those used in a Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) study (CLB-8811), also add other drugs, such as asparaginase or cyclophosphamide. Current multiagent induction regimens result in complete response rates that range from 60% to 90%.[1,4,5,11,12]

Imatinib mesylate

Imatinib mesylate is often incorporated into the therapeutic plan for patients with Ph-positive ALL. Imatinib mesylate, an orally available inhibitor of the BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase, has shown clinical activity as a single agent in Ph-positive ALL.[13,14][Level of evidence C3] More commonly, particularly in younger patients, imatinib is incorporated into combination chemotherapy regimens. There are several published single-arm studies in which the complete response rate and survival rate are compared with historical controls.

Evidence (imatinib mesylate):

Several studies have suggested that the addition of imatinib to conventional combination chemotherapy induction regimens results in complete response rates, event-free survival rates, and OS rates that are higher than those in historical controls.[15,16,17] At the present time, no conclusions can be drawn regarding the optimal imatinib dose or schedule.

- In a study of imatinib combined with chemotherapy from the Northern Italy Leukemia Group, patients with newly diagnosed, untreated Ph-positive ALL were treated with an induction regimen containing idarubicin, vincristine, prednisone, and L-asparaginase.[18] After accrual of an initial cohort, the study was modified to include the use of imatinib (600 mg qd from days 15 to 21). In consolidation, patients received imatinib (600 mg qd for 7 days) beginning 3 days before the start of each course of chemotherapy.

- For all patients who achieved remission, the intent was to proceed to allogeneic transplant when and if an HLA-matched donor could be identified. Patients lacking a donor received an autologous transplant. After completion of chemotherapy and transplant, all patients were to receive maintenance imatinib for as long as tolerated. After 20 patients had accrued to the imatinib arm, L-asparaginase was omitted from the induction regimen from both arms because of toxicity.

- Outcomes for the first cohort of 35 patients who did not receive imatinib were compared with those of the subsequent cohort of 59 imatinib-treated patients. For patients treated with imatinib, the OS probability was 38% at 5 years (median, 3.1 years) versus 23% in the imatinib-free group (median, 1.1 year; P = .009).[18][Level of evidence C1]

- The drawbacks of this nonrandomized study were the small sample size (94 total patients) and the change in the treatment regimen (omission of L-asparaginase) midway through the study. However, the results suggested that inclusion of imatinib into a relatively standard chemotherapy regimen for newly diagnosed adult patients with Ph-positive ALL may provide a significant survival advantage.

- In another study, ten patients with Ph-positive ALL and ten patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in lymphoid blast crisis were treated with doses of imatinib ranging from 300 mg to 1,000 mg per day.[13]

- Of these 20 patients, four had complete hematologic remission and ten had marrow responses.

- Responses were short lived, with most of these patients experiencing disease relapse at a median of 58 days after the start of therapy.

- In another study, 48 patients with Ph-positive ALL were treated with 400 mg to 800 mg of imatinib per day.[14]

- The overall response rate was 60%, with 9 out of 48 patients (19%) achieving a complete remission.

- The responses again were short, with a median duration of 2.2 months.

In each of these studies, common toxicities were nausea and liver enzyme abnormalities, which necessitated interruption and/or dose reduction of imatinib.[13,14] Subsequent allogeneic transplant does not appear to be adversely affected by the addition of imatinib to the treatment regimen. For more information, see Nausea and Vomiting Related to Cancer Treatment.

Imatinib is generally incorporated into the treatment of patients with Ph-positive ALL because of the responses observed in monotherapy trials. If a suitable donor is available, allogeneic bone marrow transplant should be considered because remissions are generally short with conventional ALL chemotherapy clinical trials.

Supportive care

Since myelosuppression is an anticipated consequence of both leukemia and its treatment with chemotherapy, patients must be closely monitored during remission induction treatment. Facilities must be available for hematologic support and for the treatment of infectious complications.

Supportive care during remission induction treatment should routinely include red blood cell and platelet transfusions, when appropriate.[19,20]

Evidence (supportive care):

- Randomized clinical trials have shown similar outcomes for patients who received prophylactic platelet transfusions at a level of 10,000/mm3 rather than at a level of 20,000/mm3.[21]

- The incidence of platelet alloimmunization was similar among groups randomly assigned to receive one of the following from random donors:[22]

- Pooled platelet concentrates.

- Filtered, pooled platelet concentrates.

- Ultraviolet B-irradiated, pooled platelet concentrates.

- Filtered platelets obtained by apheresis.

Empiric broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy is an absolute necessity for febrile patients who are profoundly neutropenic.[23,24] Careful instruction in personal hygiene and dental care and in recognizing early signs of infection are appropriate for all patients. Elaborate isolation facilities, including filtered air, sterile food, and gut flora sterilization, are not routinely indicated but may benefit patients undergoing transplants.[25,26]

Rapid marrow ablation with consequent earlier marrow regeneration decreases morbidity and mortality. White blood cell transfusions can be beneficial in selected patients with aplastic marrow and serious infections that are not responding to antibiotics.[27] Prophylactic oral antibiotics may be appropriate in patients with expected prolonged, profound granulocytopenia (<100/mm3 for 2 weeks), although further studies are necessary.[28] Serial surveillance cultures may be helpful in detecting the presence or acquisition of resistant organisms in these patients.

As suggested in a CALGB study (CLB-9111), the use of myeloid growth factors during remission-induction therapy appears to decrease the time to hematopoietic reconstitution.[29,30]

CNS prophylaxis therapy

The early institution of CNS prophylaxis is critical to achieve control of sanctuary disease.

Special Considerations for B-Cell and T-Cell ALL

Two additional subtypes of ALL require special consideration. B-cell ALL, which expresses surface immunoglobulin and cytogenetic abnormalities such as t(8;14), t(2;8), and t(8;22), is not usually cured with typical ALL regimens. Aggressive, brief-duration, high-intensity regimens, including those previously used in CLB-9251 (NCT00002494), that are similar to those used in aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma have shown high response rates and cure rates (75% complete response rate; 40% failure-free survival rate).[31,32,33] Similarly, T-cell ALL, including lymphoblastic lymphoma, has shown high cure rates when treated with cyclophosphamide-containing regimens.[4]

Whenever possible, patients with B-cell or T-cell ALL should enroll in clinical trials designed to improve the outcomes in these subsets.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Goldstone AH, Richards SM, Lazarus HM, et al.: In adults with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the greatest benefit is achieved from a matched sibling allogeneic transplantation in first complete remission, and an autologous transplantation is less effective than conventional consolidation/maintenance chemotherapy in all patients: final results of the International ALL Trial (MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993). Blood 111 (4): 1827-33, 2008.

- Bortin MM, Horowitz MM, Gale RP, et al.: Changing trends in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for leukemia in the 1980s. JAMA 268 (5): 607-12, 1992.

- Horowitz MM, Przepiorka D, Champlin RE, et al.: Should HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplants for leukemia be restricted to large centers? Blood 79 (10): 2771-4, 1992.

- Larson RA, Dodge RK, Burns CP, et al.: A five-drug remission induction regimen with intensive consolidation for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: cancer and leukemia group B study 8811. Blood 85 (8): 2025-37, 1995.

- Linker CA, Levitt LJ, O'Donnell M, et al.: Treatment of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia with intensive cyclical chemotherapy: a follow-up report. Blood 78 (11): 2814-22, 1991.

- Barrett AJ, Horowitz MM, Gale RP, et al.: Marrow transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: factors affecting relapse and survival. Blood 74 (2): 862-71, 1989.

- Dinsmore R, Kirkpatrick D, Flomenberg N, et al.: Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 62 (2): 381-8, 1983.

- Jacobs AD, Gale RP: Recent advances in the biology and treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. N Engl J Med 311 (19): 1219-31, 1984.

- Doney K, Buckner CD, Kopecky KJ, et al.: Marrow transplantation for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first marrow remission. Bone Marrow Transplant 2 (4): 355-63, 1987.

- Vernant JP, Marit G, Maraninchi D, et al.: Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first complete remission. J Clin Oncol 6 (2): 227-31, 1988.

- Hoelzer D, Thiel E, Löffler H, et al.: Prognostic factors in a multicenter study for treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. Blood 71 (1): 123-31, 1988.

- Kantarjian H, Thomas D, O'Brien S, et al.: Long-term follow-up results of hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (Hyper-CVAD), a dose-intensive regimen, in adult acute lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer 101 (12): 2788-801, 2004.

- Druker BJ, Sawyers CL, Kantarjian H, et al.: Activity of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in the blast crisis of chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the Philadelphia chromosome. N Engl J Med 344 (14): 1038-42, 2001.

- Ottmann OG, Druker BJ, Sawyers CL, et al.: A phase 2 study of imatinib in patients with relapsed or refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoid leukemias. Blood 100 (6): 1965-71, 2002.

- Thomas DA, Faderl S, Cortes J, et al.: Treatment of Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphocytic leukemia with hyper-CVAD and imatinib mesylate. Blood 103 (12): 4396-407, 2004.

- Yanada M, Takeuchi J, Sugiura I, et al.: High complete remission rate and promising outcome by combination of imatinib and chemotherapy for newly diagnosed BCR-ABL-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a phase II study by the Japan Adult Leukemia Study Group. J Clin Oncol 24 (3): 460-6, 2006.

- Wassmann B, Pfeifer H, Goekbuget N, et al.: Alternating versus concurrent schedules of imatinib and chemotherapy as front-line therapy for Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL). Blood 108 (5): 1469-77, 2006.

- Bassan R, Rossi G, Pogliani EM, et al.: Chemotherapy-phased imatinib pulses improve long-term outcome of adult patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Northern Italy Leukemia Group protocol 09/00. J Clin Oncol 28 (22): 3644-52, 2010.

- Slichter SJ: Controversies in platelet transfusion therapy. Annu Rev Med 31: 509-40, 1980.

- Murphy MF, Metcalfe P, Thomas H, et al.: Use of leucocyte-poor blood components and HLA-matched-platelet donors to prevent HLA alloimmunization. Br J Haematol 62 (3): 529-34, 1986.

- Rebulla P, Finazzi G, Marangoni F, et al.: The threshold for prophylactic platelet transfusions in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche Maligne dell'Adulto. N Engl J Med 337 (26): 1870-5, 1997.

- Leukocyte reduction and ultraviolet B irradiation of platelets to prevent alloimmunization and refractoriness to platelet transfusions. The Trial to Reduce Alloimmunization to Platelets Study Group. N Engl J Med 337 (26): 1861-9, 1997.

- Hughes WT, Armstrong D, Bodey GP, et al.: From the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with unexplained fever. J Infect Dis 161 (3): 381-96, 1990.

- Rubin M, Hathorn JW, Pizzo PA: Controversies in the management of febrile neutropenic cancer patients. Cancer Invest 6 (2): 167-84, 1988.

- Armstrong D: Symposium on infectious complications of neoplastic disease (Part II). Protected environments are discomforting and expensive and do not offer meaningful protection. Am J Med 76 (4): 685-9, 1984.

- Sherertz RJ, Belani A, Kramer BS, et al.: Impact of air filtration on nosocomial Aspergillus infections. Unique risk of bone marrow transplant recipients. Am J Med 83 (4): 709-18, 1987.

- Schiffer CA: Granulocyte transfusions: an overlooked therapeutic modality. Transfus Med Rev 4 (1): 2-7, 1990.

- Wade JC, Schimpff SC, Hargadon MT, et al.: A comparison of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole plus nystatin with gentamicin plus nystatin in the prevention of infections in acute leukemia. N Engl J Med 304 (18): 1057-62, 1981.

- Scherrer R, Geissler K, Kyrle PA, et al.: Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) as an adjunct to induction chemotherapy of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Ann Hematol 66 (6): 283-9, 1993.

- Larson RA, Dodge RK, Linker CA, et al.: A randomized controlled trial of filgrastim during remission induction and consolidation chemotherapy for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: CALGB study 9111. Blood 92 (5): 1556-64, 1998.

- Hoelzer D, Ludwig WD, Thiel E, et al.: Improved outcome in adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 87 (2): 495-508, 1996.

- Lee EJ, Petroni GR, Schiffer CA, et al.: Brief-duration high-intensity chemotherapy for patients with small noncleaved-cell lymphoma or FAB L3 acute lymphocytic leukemia: results of cancer and leukemia group B study 9251. J Clin Oncol 19 (20): 4014-22, 2001.

- Thomas DA, Cortes J, O'Brien S, et al.: Hyper-CVAD program in Burkitt's-type adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 17 (8): 2461-70, 1999.

Treatment of ALL in Remission

Treatment Options for ALL in Remission

Treatment options for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in remission include:

-

Consolidation therapy, including:

- Chemotherapy.

- Ongoing treatment with a BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitor, such as imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib.

- Autologous or allogeneic bone marrow transplant (BMT).

-

Central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis therapy, including:

- Cranial radiation therapy plus intrathecal (IT) methotrexate.

- High-dose systemic methotrexate and IT methotrexate without cranial radiation therapy.

- IT chemotherapy alone.

Consolidation therapy

Current approaches to consolidation therapy for ALL include short-term, relatively intensive chemotherapy followed by:

- Longer-term therapy at lower doses (maintenance therapy).

- Allogeneic BMT.

Because the optimal consolidation therapy for patients with ALL is still unclear, patients should consider participating in clinical trials. For more information, see the Treatment of Diffuse Small Noncleaved-Cell/Burkitt Lymphoma section in Aggressive B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment.

Evidence (chemotherapy):

- Several trials, including studies from the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CLB-8811) and the completed European Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG-2993 [NCT00002514]), of aggressive consolidation chemotherapy for ALL have confirmed a long-term disease-free survival (DFS) rate of approximately 40%.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7]

- In contrast, poor cure rates were demonstrated in patients with Philadelphia chromosome (Ph)–positive ALL, B-cell lineage ALL with an L3 phenotype (surface immunoglobulin positive), and B-cell lineage ALL characterized by t(4;11).

Administration of the newer dose-intensive schedules can be difficult and should be performed by physicians experienced in these regimens at centers equipped to deal with potential complications. In studies that eliminated continuation or maintenance chemotherapy, patients had outcomes inferior to those of patients in studies with extended treatment durations.[8,9] Imatinib has been incorporated into maintenance regimens in patients with Ph-positive ALL.[10,11,12]

Evidence (allogeneic and autologous BMT):

Allogeneic BMT results in the lowest incidence of leukemic relapse, even when compared with a BMT from an identical twin (syngeneic BMT). This finding has led to the concept of an immunologic graft-versus-leukemia effect similar to graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). The improvement in DFS in patients undergoing allogeneic BMT as primary consolidation therapy is offset, in part, by the increased morbidity and mortality from GVHD, veno-occlusive disease of the liver, and interstitial pneumonitis.[13]

- The results of a series of retrospective and prospective studies published between 1987 and 1994 suggest that allogeneic BMT or autologous BMT as consolidation therapy offer no survival advantage over intensive chemotherapy, except perhaps for patients with high-risk or Ph-positive ALL.[14,15,16,17] This was confirmed in the ECOG-2993 study (NCT01505699).[7]

- The use of allogeneic BMT as primary consolidation therapy is limited by both the need for an HLA-matched sibling donor and the increased mortality from allogeneic BMT in patients in their fifth or sixth decade.

- The mortality from allogeneic BMT using an HLA-matched sibling donor in these studies ranged from 20% to 40%.

- Following on the results of earlier studies, the International ALL Trial (ECOG-2993) was launched to examine the role of transplant as consolidation therapy for ALL more definitively. Patients were accrued from 1993 to 2006.[7] Patients with Ph-negative ALL between the ages of 15 years and 59 years received identical multiagent induction therapy resembling previously published regimens.[1,2,3] Patients in remission were then eligible for HLA typing; patients with a fully matched sibling donor underwent allogeneic BMT as consolidation therapy. Patients without a donor were randomly assigned to receive either an autologous BMT or maintenance chemotherapy. The primary outcome measured was overall survival (OS). Event-free survival, relapse rate, and nonrelapse mortality were secondary outcomes. A total of 1,929 patients were registered and stratified according to age, white blood cell (WBC) count, and time to remission. High-risk patients were defined as those having a high WBC count at presentation or those older than 35 years.

- Ninety percent of patients in this study achieved remission after induction therapy. Of these patients, 443 had an HLA-identical sibling, 310 of whom underwent an allogeneic BMT. For the 456 patients in remission who were eligible for transplant but lacked a donor, 227 received chemotherapy alone, while 229 underwent an autologous BMT.

- By donor-to-no-donor analysis, standard-risk ALL patients with an HLA-identical sibling had a 5-year OS rate of 53%, compared with 45% for patients lacking a donor (P = .01).

- In a subgroup analysis, the advantage for patients with standard-risk ALL who had donors remained significant (OS rate, 62% vs. 52%; P = .02).

- For patients with high-risk disease (older than 35 years or high WBC count), the difference in OS was 41% versus 35% (donor vs. no donor) but was not significant (P = .2).

- Relapse rates were significantly lower (P < .00005) for both standard- and high-risk patients with HLA-matched donors.

- In contrast to allogeneic BMT, autologous BMT was less effective than maintenance chemotherapy as consolidation treatment (5-year OS rate, 46% for chemotherapy vs. 37% for autologous BMT; P = .03).

- The results of this trial suggest the existence of a graft-versus-leukemia effect for adult Ph-negative ALL and support the use of sibling donor allogeneic BMT as the consolidation therapy providing the greatest chance for long-term survival for patients with standard-risk adult ALL in first remission.[7][Level of evidence B4]

- The results also suggest that in the absence of a sibling donor, maintenance chemotherapy is preferable to autologous BMT as consolidation therapy.[7][Level of evidence B4]

The use of matched unrelated donors for allogeneic BMT is currently under evaluation. However, because of its current high treatment-related morbidity and mortality, allogeneic BMT is reserved for patients in second remission or beyond. The dose of total-body radiation therapy administered is associated with the incidence of acute and chronic GVHD and may be an independent predictor of leukemia-free survival.[18][Level of evidence C1]

Evidence (B-cell ALL):

Aggressive cyclophosphamide-based regimens similar to those used in aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma have shown improved outcome of prolonged DFS for patients with B-cell ALL (L3 morphology, surface immunoglobulin positive).[19]

- One group of investigators retrospectively reviewed three sequential cooperative group trials from Germany and found the following results:[19]

- A marked improvement in survival, from zero survivors in a 1981 study that used standard pediatric therapy and lasted 2.5 years, to a 50% survival rate in two subsequent trials that used rapidly alternating lymphoma-like chemotherapy and were completed within 6 months.

CNS prophylaxis therapy

The early institution of CNS prophylaxis is critical to achieve control of sanctuary disease. Some authors have suggested that there is a subgroup of patients at low risk of CNS relapse for whom CNS prophylaxis may not be necessary. However, this concept has not been tested prospectively.[20]

Aggressive CNS prophylaxis remains a prominent component of treatment.[19] This report, which requires confirmation in other cooperative group settings, is encouraging for patients with L3 ALL. Patients with surface immunoglobulin and L1 or L2 morphology did not benefit from this regimen. Similarly, patients with L3 morphology and immunophenotype, but unusual cytogenetic features, were not cured with this approach. A WBC count of less than 50,000 per microliter predicted improved leukemia-free survival in a univariate analysis.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Gaynor J, Chapman D, Little C, et al.: A cause-specific hazard rate analysis of prognostic factors among 199 adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the Memorial Hospital experience since 1969. J Clin Oncol 6 (6): 1014-30, 1988.

- Hoelzer D, Thiel E, Löffler H, et al.: Prognostic factors in a multicenter study for treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. Blood 71 (1): 123-31, 1988.

- Linker CA, Levitt LJ, O'Donnell M, et al.: Treatment of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia with intensive cyclical chemotherapy: a follow-up report. Blood 78 (11): 2814-22, 1991.

- Zhang MJ, Hoelzer D, Horowitz MM, et al.: Long-term follow-up of adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first remission treated with chemotherapy or bone marrow transplantation. The Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Working Committee. Ann Intern Med 123 (6): 428-31, 1995.

- Larson RA, Dodge RK, Burns CP, et al.: A five-drug remission induction regimen with intensive consolidation for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: cancer and leukemia group B study 8811. Blood 85 (8): 2025-37, 1995.

- Kantarjian H, Thomas D, O'Brien S, et al.: Long-term follow-up results of hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (Hyper-CVAD), a dose-intensive regimen, in adult acute lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer 101 (12): 2788-801, 2004.

- Goldstone AH, Richards SM, Lazarus HM, et al.: In adults with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the greatest benefit is achieved from a matched sibling allogeneic transplantation in first complete remission, and an autologous transplantation is less effective than conventional consolidation/maintenance chemotherapy in all patients: final results of the International ALL Trial (MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993). Blood 111 (4): 1827-33, 2008.

- Cuttner J, Mick R, Budman DR, et al.: Phase III trial of brief intensive treatment of adult acute lymphocytic leukemia comparing daunorubicin and mitoxantrone: a CALGB Study. Leukemia 5 (5): 425-31, 1991.

- Dekker AW, van't Veer MB, Sizoo W, et al.: Intensive postremission chemotherapy without maintenance therapy in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Dutch Hemato-Oncology Research Group. J Clin Oncol 15 (2): 476-82, 1997.

- Thomas DA, Faderl S, Cortes J, et al.: Treatment of Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphocytic leukemia with hyper-CVAD and imatinib mesylate. Blood 103 (12): 4396-407, 2004.

- Yanada M, Takeuchi J, Sugiura I, et al.: High complete remission rate and promising outcome by combination of imatinib and chemotherapy for newly diagnosed BCR-ABL-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a phase II study by the Japan Adult Leukemia Study Group. J Clin Oncol 24 (3): 460-6, 2006.

- Wassmann B, Pfeifer H, Goekbuget N, et al.: Alternating versus concurrent schedules of imatinib and chemotherapy as front-line therapy for Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL). Blood 108 (5): 1469-77, 2006.

- Finiewicz KJ, Larson RA: Dose-intensive therapy for adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Semin Oncol 26 (1): 6-20, 1999.

- Horowitz MM, Messerer D, Hoelzer D, et al.: Chemotherapy compared with bone marrow transplantation for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first remission. Ann Intern Med 115 (1): 13-8, 1991.

- Sebban C, Lepage E, Vernant JP, et al.: Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first complete remission: a comparative study. French Group of Therapy of Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Clin Oncol 12 (12): 2580-7, 1994.

- Forman SJ, O'Donnell MR, Nademanee AP, et al.: Bone marrow transplantation for patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 70 (2): 587-8, 1987.

- Fière D, Lepage E, Sebban C, et al.: Adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a multicentric randomized trial testing bone marrow transplantation as postremission therapy. The French Group on Therapy for Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Clin Oncol 11 (10): 1990-2001, 1993.

- Corvò R, Paoli G, Barra S, et al.: Total body irradiation correlates with chronic graft versus host disease and affects prognosis of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia receiving an HLA identical allogeneic bone marrow transplant. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 43 (3): 497-503, 1999.

- Hoelzer D, Ludwig WD, Thiel E, et al.: Improved outcome in adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 87 (2): 495-508, 1996.

- Kantarjian HM, Walters RS, Smith TL, et al.: Identification of risk groups for development of central nervous system leukemia in adults with acute lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 72 (5): 1784-9, 1988.

Treatment of Recurrent ALL

Treatment Options for Recurrent ALL

Treatment options for recurrent acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) include:

- Reinduction chemotherapy followed by allogeneic bone marrow transplant (BMT).

- Blinatumomab followed by allogeneic BMT.

- Inotuzumab ozogamicin followed by allogeneic BMT.

- Palliative radiation therapy (for patients with symptomatic recurrence).

- Dasatinib (for patients with Philadelphia chromosome [Ph]–positive ALL).

- Revumenib.

- Patients who do not have an HLA-matched donor are excellent candidates for enrollment in clinical trials that are studying:[1,2,3,4,5,6,7]

- Autologous transplant.

- Immunomodulation.

- Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.[8]

- Novel chemotherapeutic or biological agents.

Reinduction chemotherapy followed by allogeneic BMT

Patients with ALL who experience a relapse after chemotherapy and maintenance therapy are unlikely to be cured by further chemotherapy alone. These patients should be considered for reinduction chemotherapy followed by allogeneic BMT.

Blinatumomab followed by allogeneic BMT

Blinatumomab is a bispecific antibody targeting CD19 and CD3. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved blinatumomab for use in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL.

Evidence (blinatumomab):

- A randomized phase III study of blinatumomab versus one of four standard reinduction regimens was conducted in patients with primary refractory disease, which was refractory to salvage, with a first relapse lasting fewer than 12 months, a second or greater relapse, or any relapse after allogeneic transplant.[9] The four regimens included the following: fludarabine, high-dose cytosine arabinoside, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor with or without anthracycline; a high-dose cytosine arabinoside–based regimen; a high-dose methotrexate-based regimen; or a clofarabine-based regimen.

- Remission rates were 43.9% for the blinatumomab-treated group versus 24.6% in the standard-treatment group (odds ratio, 2.40; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.51–3.80).

- Overall survival (OS) was superior in the blinatumomab-treated group (7.7 months vs. 4.0 months in the standard-treatment group), with a hazard ratio (HR) of .71 (95% CI, 0.55–0.93), favoring blinatumomab.

- Adverse events occurred at similar rates in both groups, and the only unique side effect of blinatumomab was cytokine-release syndrome, which was seen in 4.9% of patients.

Blinatumomab should be considered as an option for reinduction therapy for patients with primary refractory disease, which is refractory to salvage, with a first relapse lasting fewer than 12 months, a second or greater relapse, or any relapse after allogeneic transplant.[9][Level of evidence A1]

Inotuzumab ozogamicin followed by allogeneic BMT

Inotuzumab ozogamicin is an antibody-drug conjugate targeting CD22, which contains a conjugated toxin, calicheamicin. The FDA has approved inotuzumab ozogamicin for use in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL with CD22 expression.

Evidence (inotuzumab ozogamicin):

- A randomized phase III study compared inotuzumab ozogamicin with one of three standard reinduction regimens. The trial enrolled 218 patients, aged 18 years or older, who had relapsed or refractory disease and were to receive their first or second salvage regimen.[10] The three standard regimens consisted of fludarabine, cytarabine, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (FLAG), cytarabine and mitoxantrone, or high-dose cytarabine.

- Complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery rates were 80.7% (95% CI, 72.1%–87.7%) in the inotuzumab group versus 29.4% (95% CI, 21.0%–38.8%) in the standard-treatment group (P < .001).

- Progression-free survival was superior in the inotuzumab-treated group (5.0 months vs. 1.8 months in the standard-treatment group) with an HR of 0.45 (97.5 CI, 0.34–0.61; P < .001).

- Duration of remission was short in both groups; duration in the inotuzumab group was 4.6 months (95% CI, 3.9–5.4) and duration in the standard chemotherapy group was 3.1 months (95% CI, 1.4–4.9).

- Of the 48 patients in the inotuzumab arm who proceeded to transplant after therapy, 10 developed veno-occlusive disease. Of the 20 patients who proceeded to transplant after remission on the standard chemotherapy arm, 1 developed veno-occlusive disease.

- OS was not statistically prolonged in the inotuzumab group (7.7 months in the inotuzumab group vs. 6.7 months in the standard-treatment group) (HR, 0.77; 97.5% CI, 0.58–1.03; P = .04) because of a failure to meet a study-prespecified boundary of P = .0208.

- Grade 3 or higher adverse events were more common in the inotuzumab group. Veno-occlusive disease of the liver occurred in 11% of patients in the inotuzumab group and 1% of patients in the standard-treatment group.

Inotuzumab ozogamicin may be an option for reinduction for patients with relapsed or refractory CD22-positive ALL.[10][Level of evidence B1]

Palliative radiation therapy

Low-dose palliative radiation therapy may be considered in patients with symptomatic recurrence either within or outside the central nervous system.[11]

Dasatinib

Patients with Ph-positive ALL are often taking imatinib at the time of relapse and thus have imatinib-resistant disease. Dasatinib is a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor with efficacy against several different imatinib-resistant BCR::ABL1 fusion gene variants. Dasatinib has been approved for use in patients with Ph-positive ALL who are resistant to, or intolerant of, imatinib. The approval was based on a series of trials involving patients with chronic myeloid leukemia, one of which included small numbers of patients with lymphoid blast crisis or Ph-positive ALL.

Evidence (dasatinib):

- In one study, ten patients were treated with dose-escalated dasatinib.[12] Seven of these patients had a complete hematologic response (<5% marrow blasts with normal peripheral blood cell counts), three of whom had a complete cytogenetic response.

- The common toxicities were reversible myelosuppression (89%) and pleural effusions (21%).

- Virtually all of these patients relapsed within 6 months of the start of treatment with dasatinib.

Revumenib

Revumenib is an oral menin inhibitor that is approved by the FDA for the treatment of relapsed or refractory acute leukemia with a KMT2A translocation in adult and pediatric patients aged 1 year and older.

- In the phase I/II AUGMENT-101 study (NCT04065399), 104 patients with relapsed or refractory acute leukemia with a KMT2A rearrangement received revumenib. Patients had to have a corrected QT interval (QTc) using Fridericia's formula of less than 450 milliseconds at baseline.[13]

- The overall rate of complete remission (CR) plus CRh (complete remission with partial hematologic recovery) was 21.2% (95% CI, 13.8%–30.3%). The median duration of CR plus CRh was 6.4 months (95% CI, 2.7–not reached).[13][Level of evidence C3]

- Of the 83 patients who were dependent on red blood cell and/or platelet transfusions, 14% became independent of transfusions during a 56-day postbaseline period.

- Revumenib has a boxed warning for differentiation syndrome, which was observed in 29% of patients. Grade 3 or 4 differentiation syndrome was observed in 13% of patients, and one patient died (0.7%).

- Grade 3 or higher QTc prolongation was observed in 12% of patients.

- Because revumenib is metabolized by CYP3A4, the dose must be reduced in patients receiving strong CYP3A4 inhibitors. The standard dose for patients who weigh more than 40 kg is 270 mg orally twice daily, with a dose reduction to 160 mg orally twice daily for patients receiving a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor. Furthermore, the dose is adjusted according to body surface area in patients who weigh less than 40 kg.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Herzig RH, Bortin MM, Barrett AJ, et al.: Bone-marrow transplantation in high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in first and second remission. Lancet 1 (8536): 786-9, 1987.

- Thomas ED, Sanders JE, Flournoy N, et al.: Marrow transplantation for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a long-term follow-up. Blood 62 (5): 1139-41, 1983.

- Barrett AJ, Horowitz MM, Gale RP, et al.: Marrow transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: factors affecting relapse and survival. Blood 74 (2): 862-71, 1989.

- Dinsmore R, Kirkpatrick D, Flomenberg N, et al.: Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 62 (2): 381-8, 1983.

- Sallan SE, Niemeyer CM, Billett AL, et al.: Autologous bone marrow transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 7 (11): 1594-601, 1989.

- Paciucci PA, Keaveney C, Cuttner J, et al.: Mitoxantrone, vincristine, and prednisone in adults with relapsed or primarily refractory acute lymphocytic leukemia and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase positive blastic phase chronic myelocytic leukemia. Cancer Res 47 (19): 5234-7, 1987.

- Biggs JC, Horowitz MM, Gale RP, et al.: Bone marrow transplants may cure patients with acute leukemia never achieving remission with chemotherapy. Blood 80 (4): 1090-3, 1992.

- Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, et al.: Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med 371 (16): 1507-17, 2014.

- Kantarjian H, Stein A, Gökbuget N, et al.: Blinatumomab versus Chemotherapy for Advanced Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N Engl J Med 376 (9): 836-847, 2017.

- Kantarjian HM, DeAngelo DJ, Stelljes M, et al.: Inotuzumab Ozogamicin versus Standard Therapy for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N Engl J Med 375 (8): 740-53, 2016.

- Gray JR, Wallner KE: Reversal of cranial nerve dysfunction with radiation therapy in adults with lymphoma and leukemia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 19 (2): 439-44, 1990.

- Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, et al.: Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med 354 (24): 2531-41, 2006.

- Issa GC, Aldoss I, Thirman MJ, et al.: Menin Inhibition With Revumenib for KMT2A-Rearranged Relapsed or Refractory Acute Leukemia (AUGMENT-101). J Clin Oncol 43 (1): 75-84, 2025.

Latest Updates to This Summary (03 / 17 / 2025)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Treatment Option Overview for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

Revised Table 2, Treatment Options for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL), to include revumenib as a treatment option for recurrent ALL.

Revised the list of treatment options for recurrent ALL to include revumenib.

Added Revumenib as a new subsection.

This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® Cancer Information for Health Professionals pages.

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewer for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment is:

- Aaron Gerds, MD (Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries.

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations.

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/leukemia/hp/adult-all-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389171]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either "standard" or "under clinical evaluation." These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website's Email Us.

Last Revised: 2025-03-17